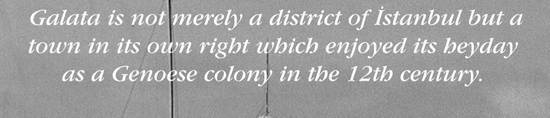

MOSAIC OF RELIGIONS AND LANGUAGES: GALATA

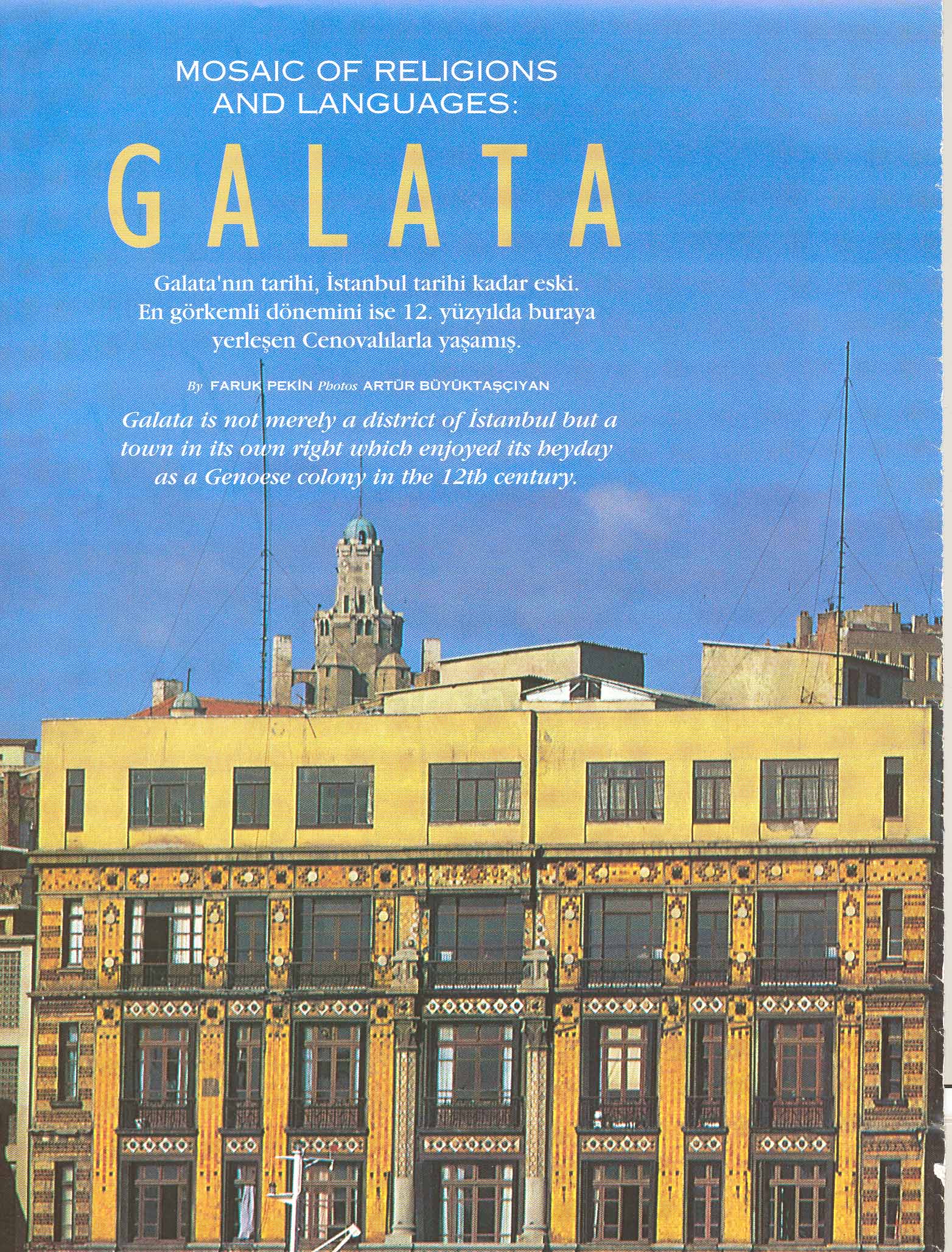

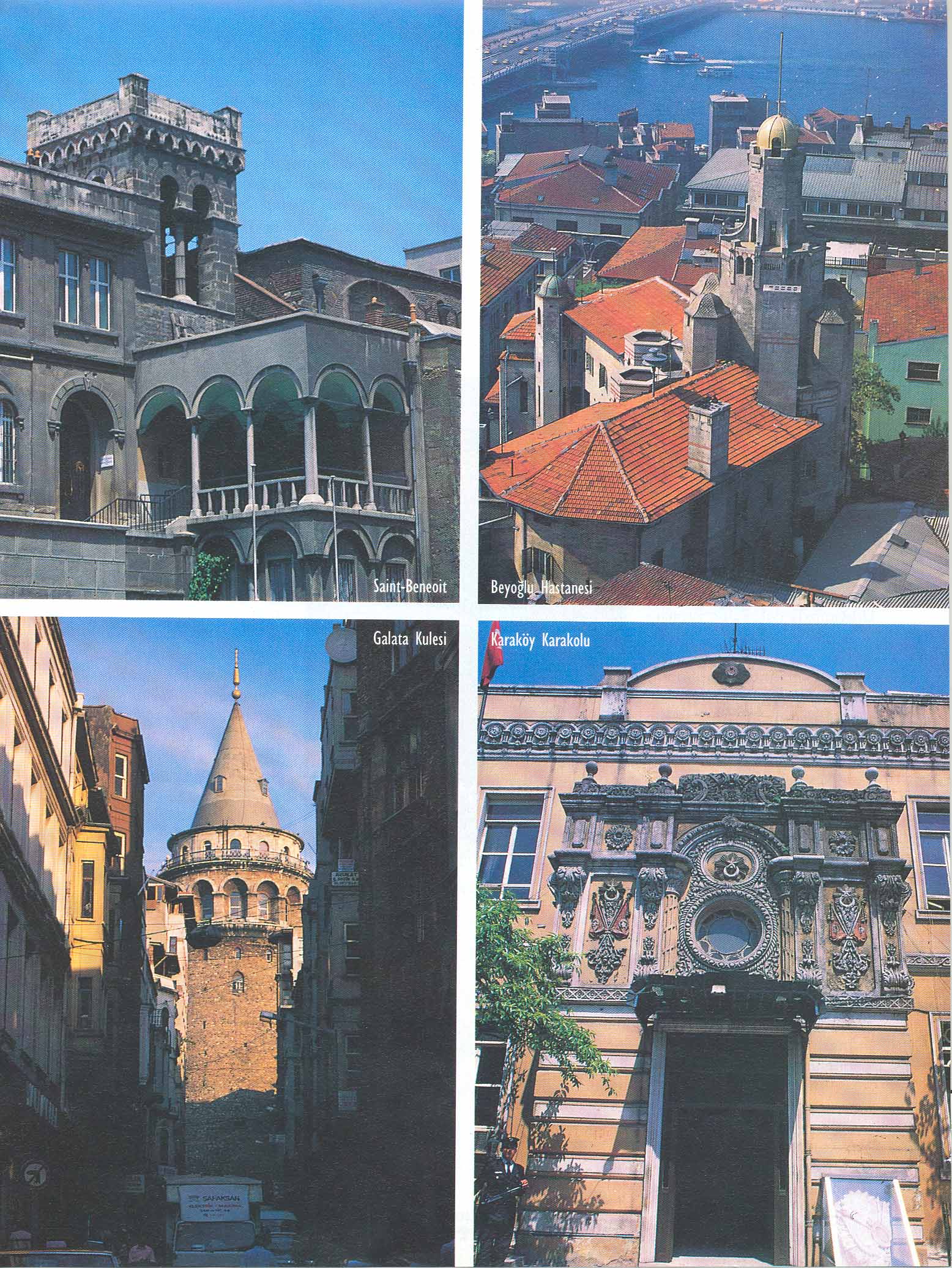

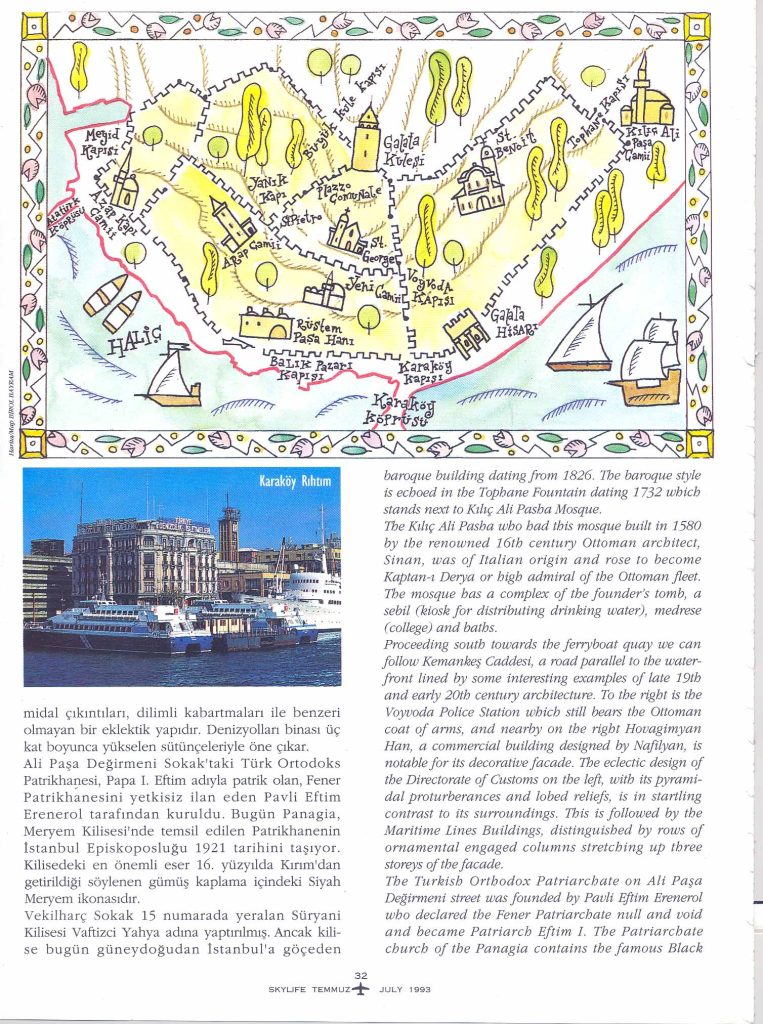

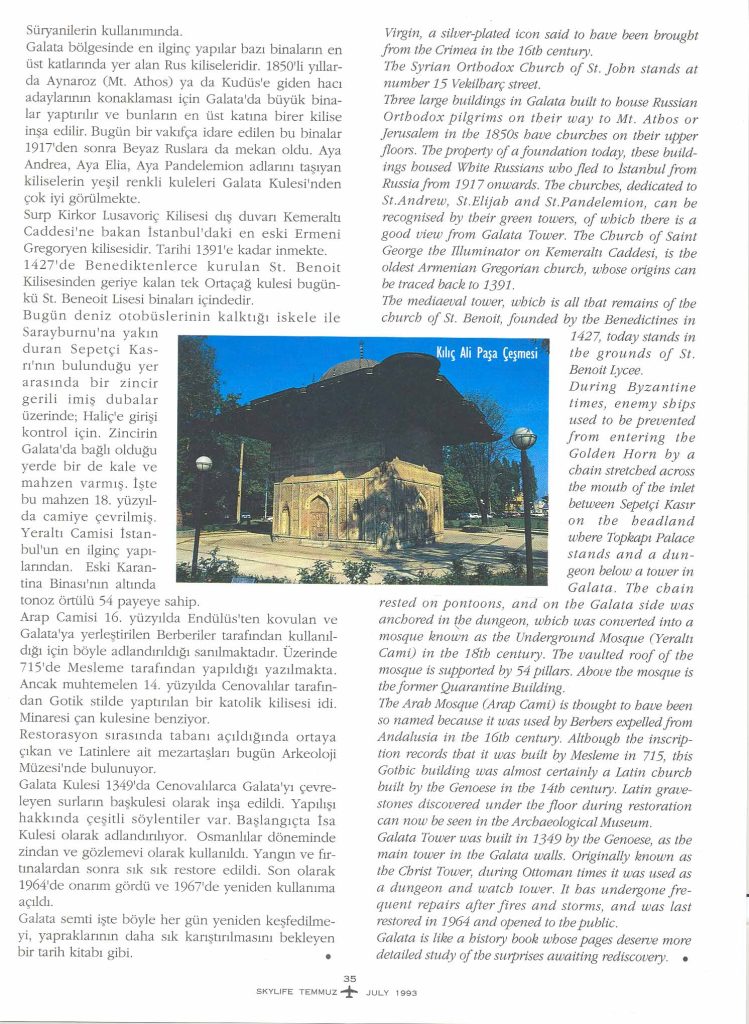

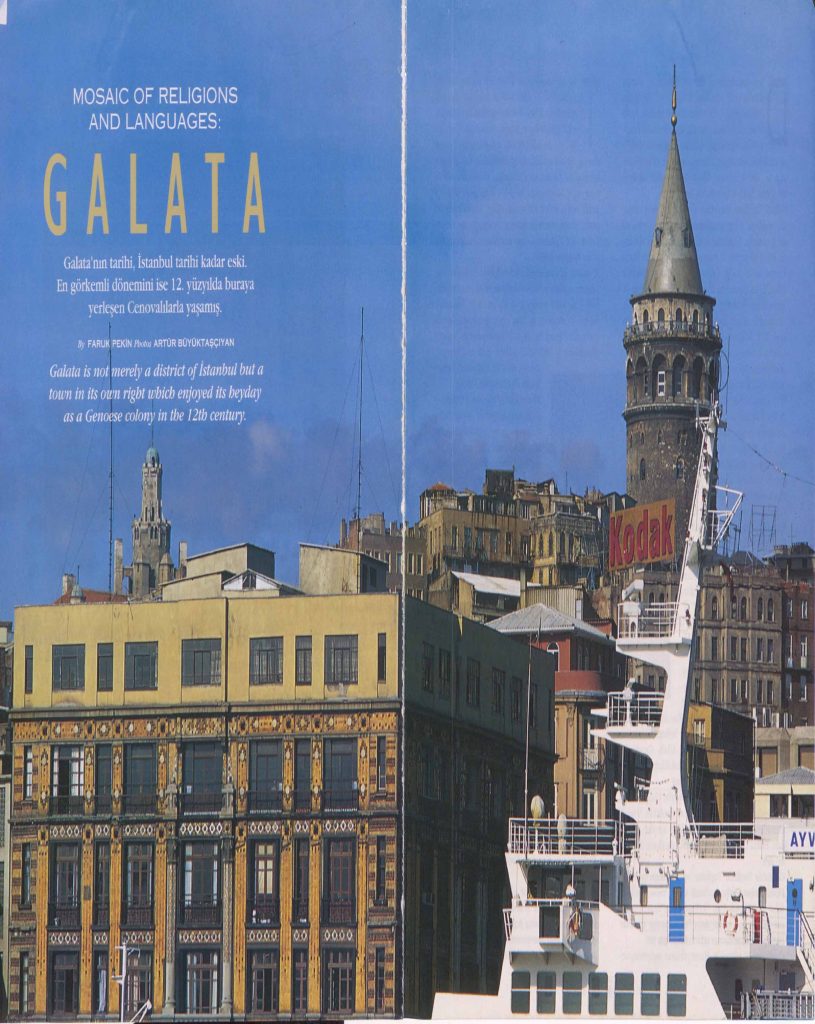

| There are some cities which are comerstones in world history. One such is Istanbul, the only metropolis which has maintained its existence, with a thriving economic, social and cultural life, for around two and a half thousand years. Facing the old walled city of Istanbul on the southem shore of the Golden Horn is Galata, once a town in its own right surrounded by 3 km long walls with 12 gates, one of which still stands today. Within the outer walls, which stretched between Azapkapı, the Galata Tower and Tophane, Galata was once divided into five areas by inner walls. A mosaic of languages and religions throughout its history, Galata remains unique in character even today. Galata ‘s history is as old as that of Istanbul, known in antiquity as Syka (from sycae meaning fig orchard). During the reign of the Byzantine Emperor Theodosius II (408-450) Galata, with its churches, forums, theatres and baths, formed Istanbul’s Thirteenth District. The origin of the word Galata is unknown. According to one theory it derives from “galaktos” (milk) after the dairies here and according to others from the Italian word “calata” meaning steps or quay. A third conjecture is that it was named after the Goths who passed through here on their way to Anatolia. Galata enjoyed its heyday under the Genoese who established a colony here in the 12th century and enjoyed an extensive degree of autonomy under the Byzantines. The Venetians wrested Galata from the Genoese for a short period, but in the 13th century we find the Genoese back in control again. A document dated 1476, 23 years after the Turkish conquest, reports that Galata consisted of 592 Greek households, 535 Turkish, 332 Frank (Gregorian, Catholic and Protestan!), Syrian Orthodox, Chaldeans, jews (Karay, Sephardic, and Eshkenazi), Arabs, gypsies, Serbians, Albanians, Wallachians, Genoese, Venetians, Frenchmen and Levantines. As a port of call for ships from all over the Mediterranean, the Black Sea and further afield, Istanbul had a floating population of foreign seamen who sought their entertainment in the “meyhanes” (literally meyhane means drinking house, more generally a restaurant where liquor and food is served together and where the incomers sit, talk and drink for long hours) of Galata. Indeed some Muslims, too, found these establishments convenient for enjoying a glass of wine without risk of reproach. According to Evliya Çelebi, “Galata means meyhanes”. The Muslim neighborhood of Galata were largely focused around Tophane and Azapkapı, where there were numerous religious and commercial buildings belonging to the Muslim community. On the whole, however, Galata was known for its Christian institutions. In the 19th century Galata underwent extensive change, as the Christian community became wealthier and began to rebuild the timber houses destroyed by fire in masonry. As drinking water was piped into more local fountains, settlement here spread northwards, and the Beyoğlu we know today evolved. Most of the embassies and new public buildings constructed by the reformist sultans preferred sites in this new area comprising Pera and Taksim, rather than Galata. Meanwhile in Galata, with its remains of Genoese walls demolished by the Ottomans, and streets which grew up on the filled-in moats, each apartment block displayed its own ethnic structure. Here were to be found the Turkish Orthodox community (which broke away from the Greek Patriarchate following the War of Independence), the Syrian Orthodox who hold their services in the Greek Orthodox Church, White Russians, Jews and Armenians. The buildings are as fascinating as the inhabitants: an underground mosque, a church on the fourth floor of an apartment building, the ancient Galata Tower, and architectural styles ranging from baroque and rococo to neo-classic Ottoman. We could take a tour of some of the principal monuments of Galata, starting from Tophane and strolling parallel to sea as far as Azkapı and from there uphill to Galata Tower. The Cannon Foundry, after which Tophane is named, was Originally built by Sultan Mehmet the Conqueror, although rebuilt and enlarged in later centuries. The Teftiş Köşk (Inspection Pamlion) which was part of the foundry complex, is now a guest house for Marmara University. It stands next to Nusretiye Mosque, a baroque building dating from 1826. The baroque style is echoed in the Tophane Fountain dating 1732 which stands next to Kılıç Ali Pasha Mosque. The Kılıç Ali Pasha who had this mosque built in 1580 by the renowned 16th century Ottoman architect, Sinan, was of Italian origin and rose to become Kaptan-ı Derya or high admiral of the Ottoman fleet. The mosque has a complex of the founder’s tomb, a sebil (kiosk for distributing drinking water), medrese (college) and baths. Proceeding south towards the ferryboat quay we can follow Kemankeş Caddesi, a road parallel to the waterfront lined by some interesting examples of Iate 19th and early 20th century architecture. To the right is the Voyvoda Police Station which still bears the Ottoman coat of arms, and nearby on the right Hovagimyan Han, a commercial building designed by Nafilyan, is notable for its decorative facade. The eclectic design of the Directorate of Customs on the left, with its pyramidal protuberances and lo bed reliefs, is in startling contrast to its surroundings. This is followed by the Maritime Lines Buildings, distinguished by rows of ornamental engaged columns stretching up three storeys of the facade. The Turkish Orthodox Patriarchate on Ali Paşa Değirmeni street was founded by Pavli Ejtim Erenerol who declared the Fener Patriarchate null and void and became Patriarch Eftim i. The Patriarchate church of the Panagia contains the famous Black Virgin, a silver-plated icon said to have been brought from the Crimea in the 16th century.The Syrian Orthodox Church of St. John stands at number 15 Vekilharç street. Three large buildings in Galata built to house Russian Orthodox pilgrims on their way to Mt. Athos or Jerusalem in the 1850s bave churches on their upper floors. The property of a foundation today, these buildings housed White Russians who fled to Istanbul from Russia from 1917 onwards.The cburcbes, dedicated to St.Andrew, St.Elijah and St.Pandelemion, can be recognized by their green towers, of which there is a good view from Galata Tower. The Church of Saint George the Illuminator on Kemeraltı Caddesi, is the oldest Armenian Gregorian church, whose origins can be traced back to 1391. The mediaeval tower, which is all that remains of the church of St. Benoit, founded by the Benedictines in 1427, today stands in the grounds of St. Benoit Lycee. During Byzantine times, enemy ships used to be prevented from entering the Golden Horn by a chain stretched across the mouth of the inlet between Sepetçi Kasır on the headland where Topkapı Palace stands and a dungeon below a tower in Galata. The chain rested on pontoons, and on the Galata side was anchored in (be dungeon, which was converted into a mosque known as the Underground Mosque (Yeraltı Cami) in the 18th century. The vaulted roof of the mosque is supported by 54 pillars. Above the mosque is the former Quarantine Bui/ding. The Arab Mosque (Arap Cami) is thought to have been so named because it was used by Berbers expelled from Andalusia in the 16th century. Although the inscription records that it was built by Mesleme in 715, this Gothic building was almost certainly a Latin church built by the Genoese in the 14th century. Latin gravestones discovered under the floor during restoration can now be seen in the Archaeological Museum. Galata Tower was built in 1349 by the Genoese, as the main tower in the Galata walls. Originally known as the Christ Tower, during Ottoman times it was used as a dungeon and watch tower. It bas undergone frequent repairs after fires and storms, and was last restored in 1964 and opened to the public. Galata is like a history book whose pages deserve more detailed study of the surprises awaiting rediscovery. . |

Önceki

Gezmek Yaşamaktır

Daha yeni

KAPADOKYA'NIN BİLİNMEYENLERİ

Bunları da beğenebilirsiniz

Bir Dünya Tiyatrosu HİNDİSTAN

6 Temmuz 2020

Yangtze Nehri’nde Yolculuk

27 Eylül 2018